The squash family (Cucurbitaceae) includes some of the most significant crops cultivated globally, playing essential ecological, economic, and cultural roles for millennia. In the American tropics, squashes were among the first cultivated crops, yet the specifics of their domestication process have remained largely unclear. A recent study by researchers at Pennsylvania State University aims to shed light on this by examining desiccated cucurbit seeds, rinds, and stems from the El Gigante Rockshelter in Honduras.

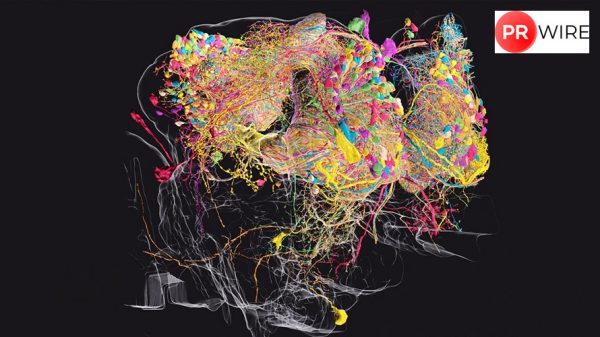

The study employs direct radiocarbon dating and morphological analyses to reconstruct human practices of selection and cultivation of three key species: Lagenaria siceraria (bottle gourd), Cucurbita pepo, and Cucurbita moschata. Radiocarbon dating reveals that humans started using Lagenaria and wild Cucurbita around 10,950 calendar years before the present (cal B.P.), primarily for non-food purposes such as watertight vessels and possibly cooking and drinking containers. Notably, a rind dated between 11,150 and 10,765 cal B.P. represents the oldest known bottle gourd in the Americas.

The findings indicate that domesticated C. moschata appeared around 4,035 cal B.P., followed by domesticated C. pepo around 2,190 cal B.P. These domesticated varieties were associated with increasing evidence for their use as food crops. Multivariate statistical analysis of seed size and shape showed significant variability within the archaeological C. pepo assemblage, representing at least three varieties: one similar to present-day zucchini, another like present-day vegetable marrow, and a native cultivar without modern analogs.

This research supports the hypothesis that Indigenous cucurbit use began in the Early Holocene, and agricultural complexity during the Late Holocene involved selective breeding that encouraged crop diversification. These findings align with previous studies that have explored the domestication of cucurbits and their ecological roles. For instance, earlier research identified that the bottle gourd, indigenous to Africa, reached East Asia and then the Americas by 10,000 B.P., suggesting human-mediated dispersal[2]. This study also found that bottle gourds and dogs were domesticated long before any food crops or livestock species, highlighting their utility for early human populations.

Further, the genus Cucurbita has been shown to contain numerous domesticated lineages with ancient New World origins. Previous research hypothesized that Holocene ecological shifts and megafaunal extinctions severely impacted wild Cucurbita, whereas their domestic counterparts adapted through symbiosis with human cultivators[3]. This new study from El Gigante Rockshelter provides concrete evidence supporting this hypothesis by showing the timeline and morphological changes in domesticated cucurbits over thousands of years.

Phylogenetic studies also play a crucial role in understanding plant domestication by resolving relationships between crops and their wild relatives. Earlier research on Cucurbita crop lineages and their wild relatives suggested histories of deep coalescence, complicating the identification of the genetic origins of these crops[4]. The new findings from El Gigante Rockshelter add to this understanding by providing direct archaeological evidence of domestication processes and the resulting crop diversity.

In summary, this study from Pennsylvania State University integrates radiocarbon dating and morphological analyses to provide a detailed timeline of cucurbit domestication in the American tropics. It confirms that Indigenous peoples began using cucurbits in the Early Holocene and that selective breeding during the Late Holocene led to significant crop diversification. These findings are consistent with earlier research on the domestication and ecological roles of cucurbits, offering a more comprehensive understanding of their historical significance.

The article originally appeared on Natural Science News.